Bronx-b

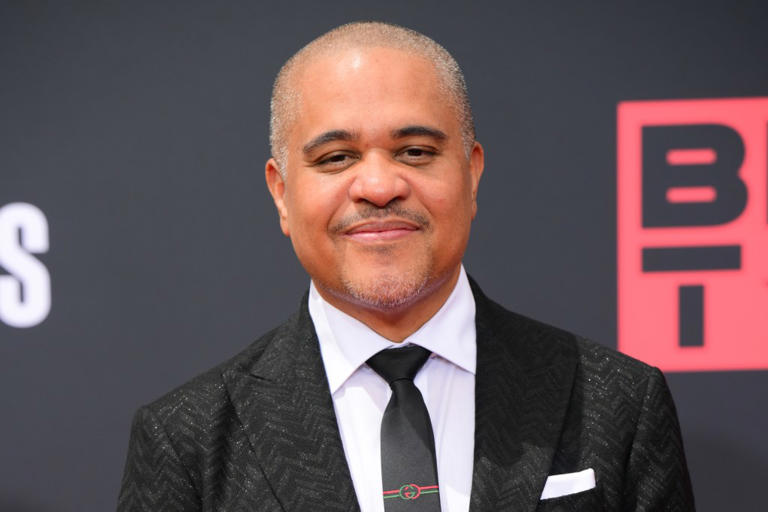

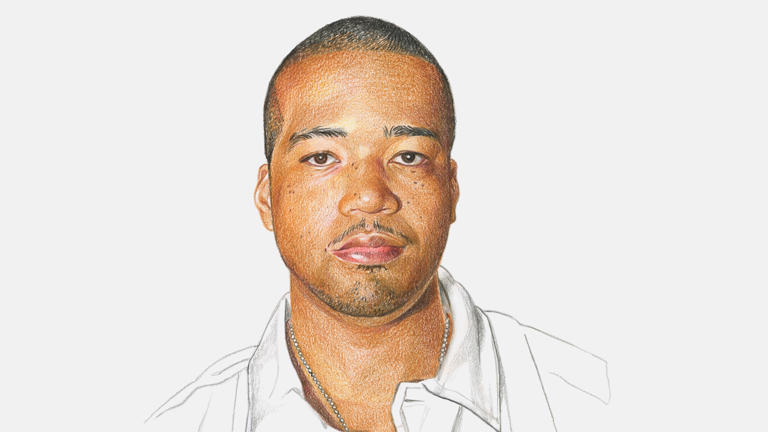

orn Chris Lighty founded Violator Management with Mona Scott-Young in 1996 — and within months they had one of the most powerful firms in the hip-hop business, with a roster that grew to include 50 Cent, LL Cool J, Busta Rhymes, Missy Elliott, A Tribe Called Quest and many more. During those years, Lighty negotiated 50 Cent’s deal with Vitaminwater — which ended up netting the rapper a reported $100 million — and over the course of his career worked at Rush Management and Def Jam, Jive and Loud Records, before his death in 2012.

Scott-Young left Violator in 2005 to branch into the television world — although she continued to co-manage Busta and Missy, the latter to this day — and her production company Monami Entertainment hit the jackpot with “Love & Hip Hop,” which has spawned a slew of spinoffs and launched stars like Cardi B.

As part of Variety’s “50 Greatest Hip-Hop Executives of All Time” feature, Busta and Scott-Young both remember Lighty, him with a written piece (with his distinctive voice loud and clear) and her in a Q&A. We’ll let them take it from here …

Chris Lighty is truly the greatest manager that has ever lived.

I met Mona Scott-Young because of Chris Lighty.

Chris Lighty is a Taurus like me.

Chris is the big brother I never had.

I am one of the first Violator artists. When Rush Management was coming to an end, Lyor Cohen asked the reps which artists they would take with them to start their own shit.

Chris said the Jungle Brothers, A Tribe Called Quest, De La Soul and us, Leaders of the New School, and started Violator. The others went in different directions, and when Leaders of the New School broke up, I stayed with Chris.

At this point, I was the only Violator Management artist.

What I was fortunate to have with Chris was his undivided attention.

His care. His education.

That big brother that I wish I had. Leadership.

He had the streets, and he had my back.

And what happened with me and him was my first solo album was a success and is what contributed in the most significant way to the growth of Violator.

Every artist saw what he did with me and what I did with him, and it helped Violator become one of the world’s biggest management companies.

When Mona Scott-Young and Chris Lighty got together, they created something that had never been seen on that level before. There will never be another Violator.

And there will never be another movement that can compete or compare to the level of greatness of Chris and Mona as individuals.

And especially how unfuckwitable they were when they were together.

I love them so much. They were everything to a lot of our lives.

Rest in Peace to the greatest to ever do it, Chris Lighty, and I’m grateful still to have Mona Scott-Young as a part of my evolution.

Violator for life!

Mona, when did you first meet Chris or become aware of him?

Oh, wow, it feels like a lifetime ago. I started out working with a group of producers from Brooklyn called the Trackmasters, and they had worked with a group called the A.T.E.E.M., and the members of that group ran in the same circles with Chris. So when we first connected, it was purely on a social level.

Around ‘95 or ‘96, the Trackmasters were going their separate ways and I was figuring out what’s next, and Chris was also in a place of transition. At the time, he was part of Rush Management, which was set up with Def Jam, but they were dismantling Rush and moving Russell and Lyor and everyone over to Def Jam fully. Chris had set up his Violator Records through Def Jam, and he asked me to come on board. When I got there, we realized that all these acts coming from Rush were now going to be in the market for management, and I just floated the idea, “Why don’t we just start Violator Management?” And that was kind of the genesis of not only our connection, but how that partnership began.

So your first acts were Busta Rhymes and A Tribe Called Quest?

I feel like we had more artists than that, but it was a very 360 relationship, I’ll put it that way. Chris came from the school of life where anything and everything that needed to be done for the artists, we would just roll up our sleeves, and there were no clear lines of delineation. So, like for Foxy Brown, she was signed to Violator Records, but I remember running around, getting her wardrobe for her video shoots because it was all hands on deck.

That’s the way we operated — it was a functional dysfunction, right? Organized chaos! The reason he managed to juggle these different entities so seamlessly and symbiotically was because, even though you might think that there would have been some kind of conflict of interest, he understood one benefits the next — how to put the pieces together so that they all worked in concert for greater good. I think the premise of Violator was built on taking different brands and different artists, putting them under one umbrella and creating an aesthetic and a movement under that umbrella. The label, the management, Def Jam, it all worked hand in hand for the greater good. Every artist benefited from the halo effect of what the success of one entity brought to the next. I think the model was unique to Chris’ ability and acumen as a diplomat. This was a guy who understood how to create a cooperative environment and manage all of the personalities involved, and do it in a way that was mutually beneficial. It was like a win for one was a win for all.

Do you think what do you think was his greatest gift? Figuring out how to get the best out of people?

I think that was part of it. But the other thing is, Chris had this sense that anything and everything is possible. That was infectious. You know, I fancy myself a maverick, but … in the early time when hip-hop was still the wild west, he saw the opportunity to formalize the way the business was structured. And that was the beauty of our partnership, where I was able to build out and maintain the back end — the day to day running of the company — while Chris was able to harness the talent and get help them through their creative process to deliver on the front end. At the time, guys were still running around with what we call the “My mans and ‘em” mentality — you know, where an artist came with his crew from the neighborhood and felt they felt could represent them in corporate America. That wasn’t always the case! And Chris understood that there was a business to this and set out on improving his own skill sets.

This is just a personal anecdote, but I’ll never forget, Chris had a stack of books with everything from understanding the mechanics of music publishing to grammar and self-help. He was just always on a quest for betterment — not only for himself, but so that he could represent his clients and represent the businesses to the best of his ability. I think people felt that passion and that earnest desire to win, and gravitated to it. He wanted everyone around him to win. That’s what gave him the ability to navigate people into the opportunities that he did, and to have the level of clientele that we had for so many years.

How big did the roster and the staff get?

What was great was we had our stable roster of clients — the do-or-dies, right? And then we had the folks that came in because they wanted help to get a deal done or they just wanted to give their careers a boost, because for the most part we did things on a handshake. You didn’t have to stick with us for life, it just had to be for the amount of time that it made sense for us both. So we contracted and expanded exponentially over the years — and as for how many, wow, sometimes it gets overwhelming even to think about it, like “Were we really juggling that many acts?!” And for employees, there was probably a minimum of 50. We had a promotions team, because this was the age of guerilla marketing, where we were out there pounding the pavements, in the clubs, handing out flyers and mixtapes. There were extended teams that were out on the road with the artists — road managers, tour managers, security personnel. So it got extremely large, but still at the core was the family dynamic, with Chris as the dad and Mona’s the mom.

And you guys were on top of the world — what led to you splitting off to do different things?

Well, Chris had branched out and started a marketing agency, and we had partnered with [CAA chief] Michael Ovitz in Hollywood, and I kind of got bitten by the bug. I really enjoyed the process of creating and producing the show “Road to Stardom” for Missy Elliott, which aired on UPN. I felt like there were more things that I wanted to explore and do. And sometimes, you know, you just feel like it’s time for us to expand and broaden and maybe not together. We still remained friends, and we kind of split the baby because I was still involved with Busta and Missy, and he had focused his attention more around the branding company that he built.

Anything else you’d like to say about him?

I want people to remember that this guy changed the culture. He impacted so many lives, not only from a business level — what he contributed to both the artists and the music — but he was just a really good guy. He cared deeply about his family, took care of everyone who came into his circle, you know. When I say he was “the dad to my mom,” I mean that in every sense of the word, because it was everything from, “Hey, I can’t pay the mortgage this month” to “I need a new book” to “My publishing deal needs to get renegotiated.” And sometimes in this dog-eat-dog world that we navigate every day, you get hardened, and it’s hard to remain a nice guy, and continuously care about the people that you work with, and people in general. But I think Chris had this, innate ability to straddle between being a hard, take-no-prisoners, no-bullshit exterior, but still maintain being a really good person who cared about the people that he worked with, all the way to the end.